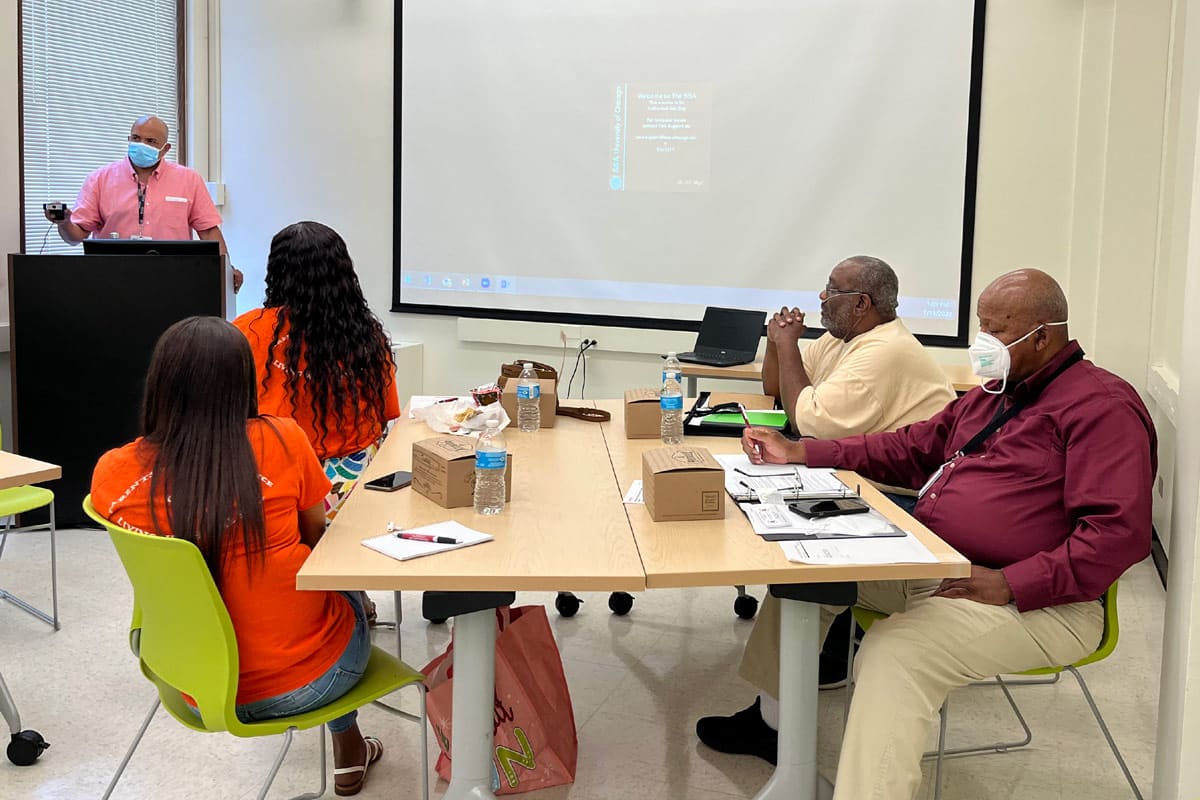

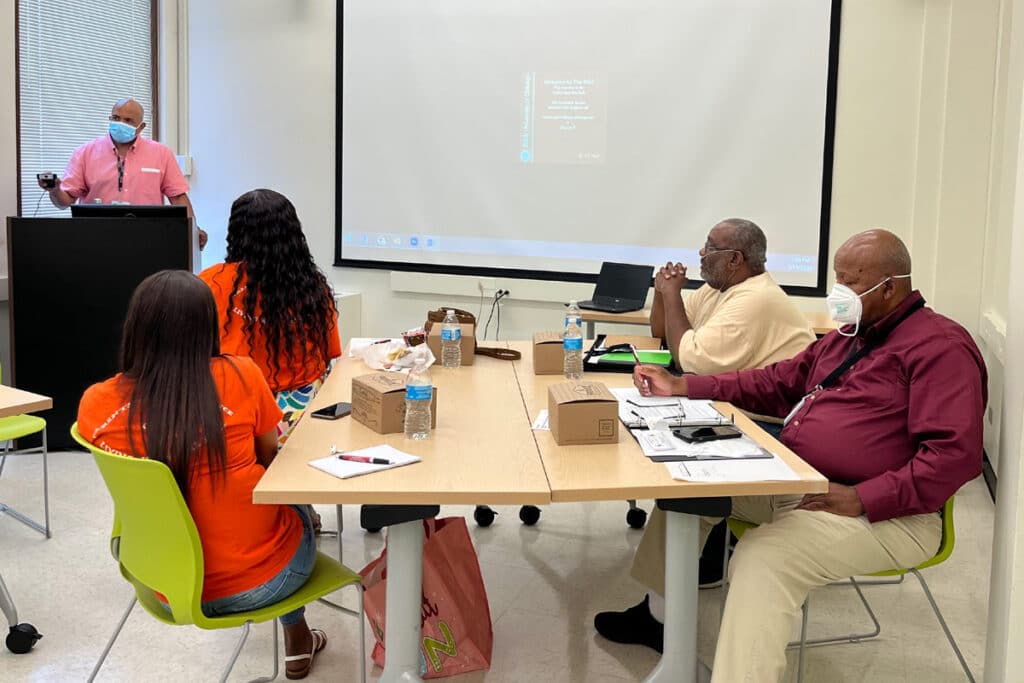

On Tuesday, July 19th, Peace Fellows and members of the community met with University of Chicago Medicine’s Violence Recovery Program (VRP). The event was held as part of the Mutual Aid Collaborative’s Civic Leader series, which aims to build connections between individuals and organizations that work to build peace and prevent violence. At their meeting, Peace Fellows spoke with Dr. Franklin Cosey-Gay, the Director of the VRP as well as Carlos Roble, a Clinical Lead/Social Worker in the VRP. Fellows learned about what the hospital does for victims of intentional violence as well as some of the root causes of violence that the Violence Recovery team hope to address.

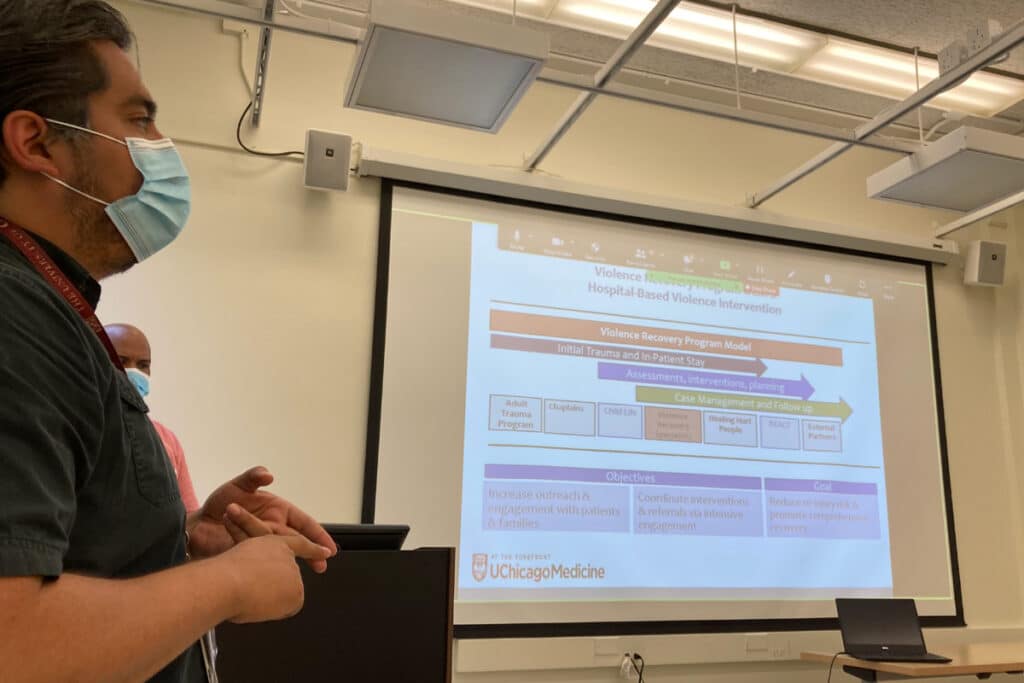

Dr. Cosey-Gay walked Peace Fellows through the history of the Violence Recovery Program at the University of Chicago Medical Center and began by discussing the structural issues that the Program was designed to address. The VRP was started in 2018, with only two violence recovery specialists involved. The trauma center was created to provide more equitable access to high-quality health care and trauma treatment services on Chicago’s South Side, specifically neighborhoods impacted by systemic violence. The VRP team views violence through a public health lens, which aims to address structural causes of violence, rather than blaming the individual. Because of this, the VRP seeks to make adjustments to the medical system that provide services to individuals affected by violence to promote equity and reduce the outbreak of further violence.

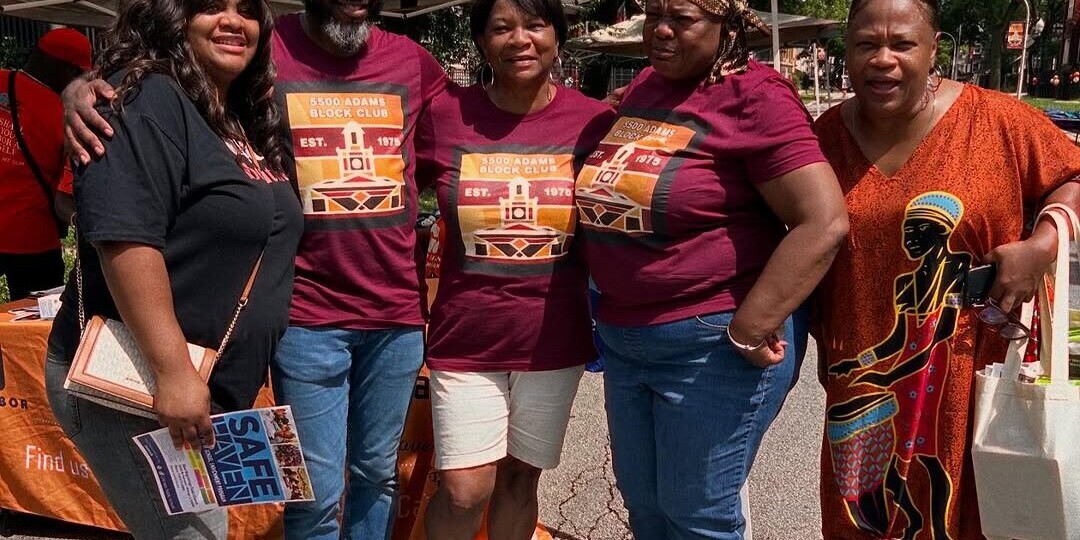

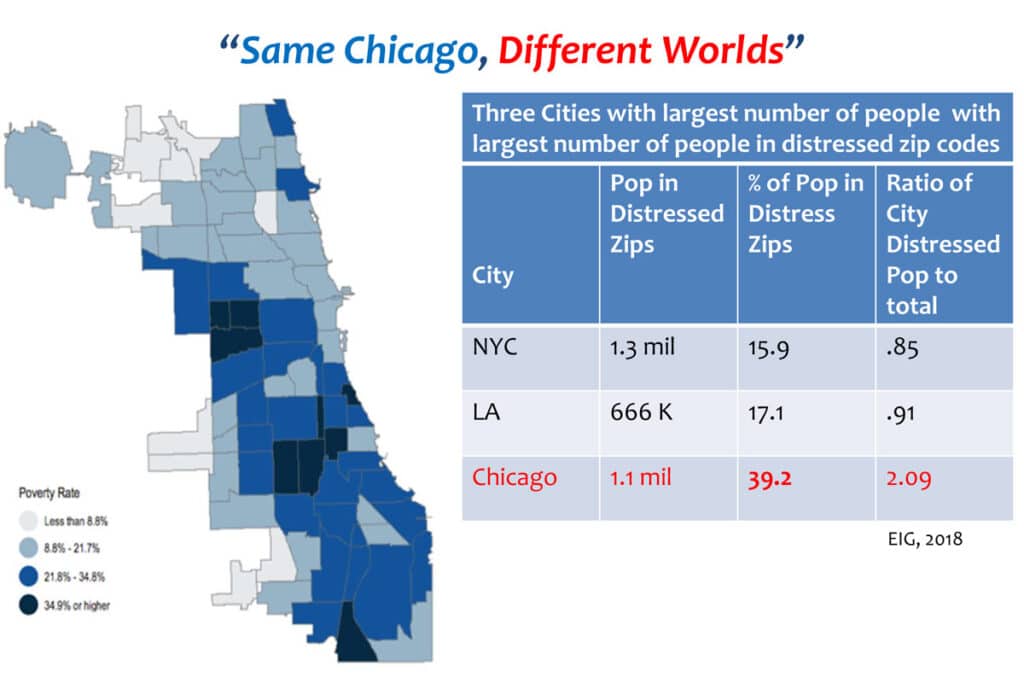

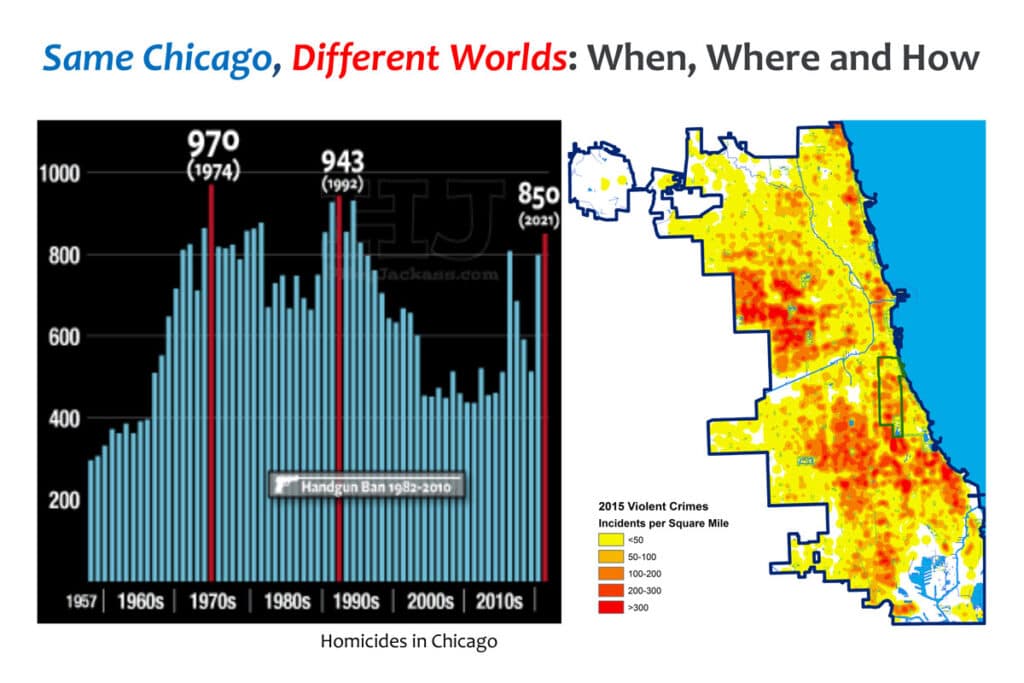

The Violence Recovery Team stressed that their framework of understanding violence through a public health framework goes beyond understanding treatment and rehabilitation on an individual level but also aims to prevent violence through examining relational, communal, and societal factors. Their presentation focused on why there are higher risk factors of violence on the Southside and particularly in predominantly Black neighborhoods. Chicago has a history of racial tensions that developed over time through restrictive covenants, redlining, urban renewal projects, and policing. These structural forces have deeply impacted South Side communities and the VRP is hoping to rebuild trust in public health institutions by gaining credibility and working with community based organizations. Meeting with Peace Fellows and members of the community acted as a way for the VRP to continue building credibility with organizations that work in violence prevention so that they can collaborate to address violence as a public health concern.

The Violence Recovery Program also operates on an individual level, acting to protect victims of violence and their families from disruptions that can be physically or emotionally harmful.

“Violence Recovery is about public health. We don’t focus on fault or blame, we focus on prevention.” — Dr. Cosey-Gay

Dr. Cosey-Gay emphasized since the role of the Violence Recovery team is to act as public health professionals, they “neither determine fault nor place blame, but focus on prevention.” Oftentimes, social workers in the VRP act to keep police away from victims of violence so that they have time and space to heal and are given time to recover before questioning. Carlos Robles, a social worker in the VRP noted:

“We don’t want to treat victims of violence as criminals, but as experts in their own lives.”

Today the Violence Recovery Program at University of Chicago Medicine has 15 full-time employees and offers 24-hour care to victims of intentional violence. Their care extends outside of the hospital as they also help patients and families navigate external health care and social services. As Peace Fellows and community members got to know the services of the VRP, they were surprised at the amount the program has grown in the last four years. Many of the attendees shared their own experiences navigating hospitals alongside victims of intentional violence and welcomed the new approach to violence recovery offered by the program. One attendee told a story about how she was not offered an opportunity to see her son’s body after he was the victim of violence and emphasized how traumatic this experience was for her. If a violence recovery program had been in place, some of the trauma of this experience could have been avoided and more trust could have been built between the hospital and the community.

Getting to know the services and history of the Violence Prevention Program helped Peace Fellows and community members build a mutually beneficial relationship with the hospital. By gaining connections to community-based organizations the VRP builds credibility and gains new resources to direct victims of violence to with the aim of preventing further violence. Members of the community similarly benefited from learning about how approaches to treating intentional violence have improved over time and from gaining a better understanding of how the trauma center could treat members of their communities. Through this meeting, Peace Fellows gained new opportunities for collaborations that have the potential to bring lasting peace to their communities.