The Chicago Peace Fellows visited the Field Museum of Natural History on June 19, 2019, for a guided tour of the “Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman” and discussion on the theme of the Role of Race and Representation in Peace Building with museum staff.

The exhibit brings to the public the controversy around the collection of bronze statues created by artist Hoffman in 1933, depicting people from different cultures across the globe, men and women, indigenous as well as white Europeans, including busts as well as figures in dramatic poses and conducting daily activities such as agriculture and hunting. The exhibit, originally called “The Races of Mankind,” was popular for decades, but later became the subject of a national anti-racism campaign and ultimately was put into storage. Recently, in an effort to account for the past and improve the museum’s connection with Chicago’s communities, the statues were brought out of storage and placed in a new context that features explanatory signs recounting the statues’ divisive history, and the Peace Fellows were asked by museum staff to provide their comment and critique.

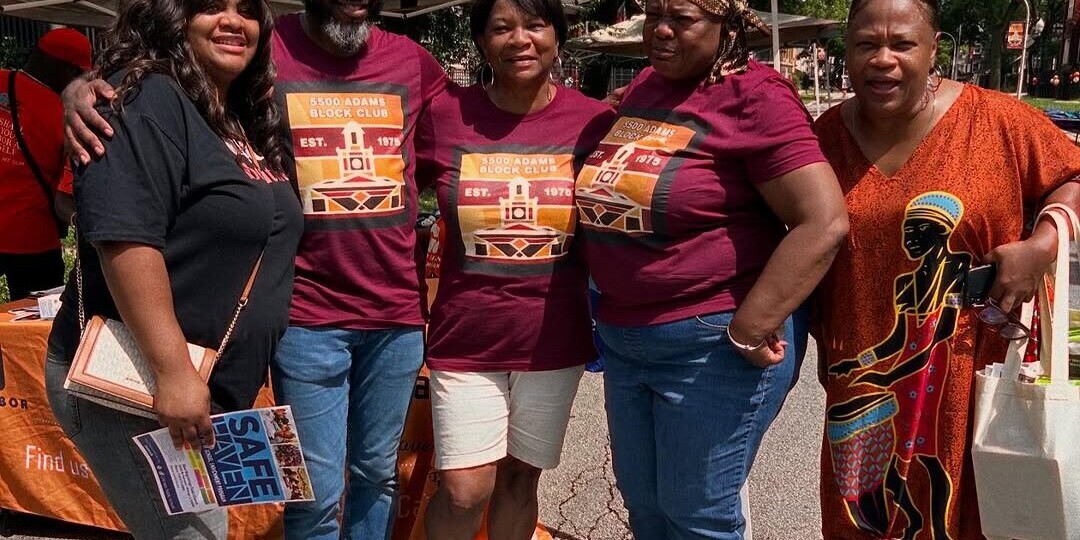

The Field Museum’s Alaka Wali, curator of North American Anthropology, and Jacob Campbell, an urban environmental anthropologist with the Keller Science Action Center, hosted Fellows Frank Latin, Dawn Hodges, Pamela Phoenix, Jackie Moore, Jamila Trimuel, Gloria Smith and Robert Biekman along with GATHER alumnus Raymond Richard as well as photo artist Cecil M Donald; Deborah Bennett, senior program officer at the Polk Bros. Foundation; Kristen Mack, senior communications officer at the John D. and MacArthur Foundation; John Zeigler, director of the Egan Office of Urban Education and Community Partnerships at DePaul University; artist Mike Bancroft; and a delegation from the Goldin Institute led by Founder and Board Chairwoman Diane Goldin; Executive Director Travis Rejman; Chief of Staff Oz Ozburn; Delasha Long, media and content specialist; and Burrell Poe, coordinator of the Chicago Peace Fellows.

The meeting took place on Juneteenth, the anniversary of the date many African Americans discovered they had been freed by the Emancipation Proclamation during the Civil War, and Alaka and Jacob welcomed the group in a Maori House built in 1881 on Tokomaru Bay, one of only four such Maori meeting houses outside of New Zealand. Jacob explained that the Field had acquired the house without consulting its Maori builders, but as the culture within the museum changed, they sought out leaders of the Tokomaru Bay communities and developed a relationship with them, ultimately securing permission to keep the house at the institution, albeit with instructions on how to properly respect and care for the structure.

[quote]“The Field Museum was built as a colonial institution. The question about this exhibit and ‘The Races of Man’ is ‘Do they transcend that colonial burden?’ And how do we make them transcend? How do we repurpose an old and problematic collection?” — Alaka Wali[/quote]

The group then toured “Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman,” as Alaka explained the statues had originally been used for “an explicitly racist purpose” despite the ambivalence of the artist, with the statues arranged in a way to show a purported hierarchy of human ‘types.’ Once prevalent among intellectuals, the idea of an evolutionary hierarchy among humans was thoroughly discredited as racist, and the exhibit was put away in 1969. But in 2016, the statues were restored and placed back on display with explanatory signs.

The Peace Fellows and the Field staff then returned to the Maori House for an extensive conversation. Frank Latin began by citing a recent study about Contract Buying in Chicago entitled “The Plunder of Black Wealth in Chicago” by Samuel DuBois at the Cook Center on Social Equity at Duke University and mentioned a forthcoming documentary about the topic from filmmaker Bruce Orenstein, artist in residence at Duke. Contract Buying was a discriminatory practice of home selling that cost tens of thousands of African American families somewhere between $3.2 to $4 billion during the 1950s and 1960s.

[quote]“I’m seeing how much institutions like this contributed to what we see today. We’re dealing with the after-effects.” — Frank Latin, Chicago Peace Fellow[/quote]

Cortez Watson, a new staff member of The Black Star Project, mentioned the Black List series on HBO as a useful counter-narrative to “The Races of Man,” noting that Volume One is available without charge on Vimeo.

Robert said that he was particularly affected by one statue, a bust of Ota Benga, an African man who had been placed in a cage in the Bronx Zoo in 1906 before protests led by African American-owned newspapers and advocacy organizations forced his release. As a resource, Robert recommended a book by African American advertising executive Tom Burrell entitled “Brainwashed” and a video discussing his work.

“We need to continue the struggle,” Robert said. “The struggle is real and deep.”

Jackie Moore said she was disappointed with the exhibit’s efforts at contextualization and worried that the statues were only perpetuating rather than dispelling stereotypes. She also urged the Field Museum to ensure that its admission prices were not preventing members of the community from seeing its exhibits. “All I saw was a different flavor of the same ice cream,” Jackie said.

[quote]“It makes me think, ‘What scientific racism are we being fed today? — Deborah Bennett, Polk Bros. Foundation”[/quote]

GATHER alumnus Raymond Richard recounted his personal journey through the criminal justice system to advocate for rights and opportunities for returning citizens, and said the exhibit opened his eyes to the historical challenges faced by African Americans, particularly African American women.

“We don’t know our history,” Ray said. “If young people knew, they might make change.”

DePaul’s John Ziegler said the exhibit raised many important questions, especially “How do we begin to disrupt this narrative?”

“The thing that is really disturbing is that this is the Field Museum – you’re supposed to come here to learn something.”

Jamila Trimuel discussed a statue of a young Ethiopian woman, whose hair was braided in a style similar to that used by African American women today, explaining that American corporate culture continues to discriminate against African American women while American culture as a whole defines African American women as unattractive. “We have not grown,” Jamila said. “I could not have worn the hair style my sister rocked all those years ago.”

Dr. Pamela Phoenix said she was particularly disturbed by a statue of a naked white European man in an athletic pose.

“It looked like he was the hero,” Pamela said. “I thought, ‘Not this story again.’”

Several participants mentioned the connection to the conversation around reparations and the testimony of Ta-Nehisi Coates at the House of Representatives and his Case for Reparations from the June 2014 issues of The Atlantic, while others noted the resonance with the ongoing debate to remove Confederate Statues across the country.